The Case for Going Beyond the Base

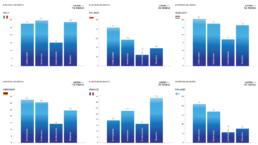

Listen To People Analysis

Your base is your core audience – they are reliable in their support. They rarely need to be persuaded, but rather need to be mobilised. There are a few common traps that campaigners, activists and communicators can fall into when dealing with their base.

One is over-serving. It feels nice to preach to the choir, but you will get more done by expanding your base, building coalitions across new audiences and even starting conversations with those who disagree with you.

Another is approaching your base the wrong way. Generally speaking, your base is not to be persuaded as they are already on side. Rather it is to be mobilised – to vote, to volunteer, to participate.

In this piece, I lay out how to think about reaching beyond your base – how to define new audiences, how to approach and mobilise them, and finally a few interesting findings based on our own audience research in Europe.

Defining audiences

If our goal is to influence societal narratives at scale we need to know who our audience is, what they care about, where to go to connect with them, and what type of message will resonate with them. This is not necessarily a straightforward exercise.

There are many ways to approach this task and many data sources to draw on. Our latest work at EMI drew on a combination of polling data, focus group research, media listening research, and campaign testing. Then, once we had this data, we had to sort it.

One useful way (I believe originally developed by the European Parliament’s DG COMM) is to break a (European) country’s population into four overall segments. The divisions are based on attitudes towards democracy, the EU, and several other core values and attitudes. With this method, we can define a national audience as being:

- An Enthusiast (supporter, core audience/base) likes democracy and the EU, as well as diversity, equality, environmental protection, and international solidarity and cooperation (all the good stuff). These issues are a priority.

- A Moderate (lean supporter) can be persuaded to like democracy and the EU, and the other issues. However, this is not a priority, as they are busy with their daily lives, including work and family. However, certain issues can trigger them either way.

- An Ambivalent (lean opposition) is more sceptical of democracy and the EU, but like the Moderates, they are busy with their daily lives, so this is not their priority. However, certain issues can trigger them either way.

- A Sceptic (opposition) does not like democracy or the EU, and actively works against most the things an Enthusiast works for. They tend to be authoritarian, favour “strong” leaders, and usually dislike immigrants and women’s rights, in particular. This is usually where disinformation originates, and they are often very organised in their disinformation and trolling actions, as they try to negatively influence public narratives.

From this broad categorisation, we can break down target audiences even further – but using these definitions as our anchor in how to approach and conceive of particular audiences and how to approach them.

Application and practice

As you see from the numbers above (source: Listen To People), the situation varies greatly depending on the country you are in. The key to interpreting these numbers is by making two comparisons. First Enthusiasts Vs Sceptics, which will define how large our supporter base is compared to our opposition’s. Then Moderates Vs Ambivalents, which indicates how “easily” one can persuade a larger middle audience to support your cause.

For example, the Finns are largely lean democratic/EU supporters [Enthusiasts (42%) + Moderates (33%) v. Sceptics (15%) + Ambivalents (11%)]. This is good, as Finnish society is generally more pro-democratic, not as polarised, and most Finns are generally more friendly towards democracy and the EU. When it comes to what resonates, Finns care deeply about social and income inequality, as well as the climate emergency, so campaigning on these issues to Enthusiasts, Moderates, and even Ambivalents, can work well if done right and tailored properly.

These segments can (and should) be broken down even further to be applied in your day to day campaign work. An EU Enthusiast is a broad category – fundamentally it simply means that they think the EU makes the world a better place. They tend to believe in strong democracies, respect for human rights, equality, diversity, environmental protection, international cooperation and cooperation on global issues.

EU Enthusiasts tend to be politically active, but do not perceive themselves as being activists and simply support pro-democratic political parties and discuss issues with friends and family around the dinner table. A relatively small subsection may include activists fighting for causes such as climate justice, environmental justice, social justice, gender equality, LGBTI+ rights, migration and so on – but if we want to speak beyond our base, we must understand that even our enthusiastic supporters are not necessarily mobilised or can relate to the activist experience.

Tips and tricks for getting it done.

So what’s next? Below I add a few things we learned from the data and some tips for communicating beyond the base – and opportunities for getting involved with what EMI has coming up.

- Contact EMI so we can make sure to add you to the upcoming Democracy Tables – a series of discussion groups devoted to breaking down and exploring applications of data we are making available as part of Listen to People.

- Don’t use visuals of demonstrations if you want to appeal to middle audiences – especially if they can be interpreted as potentially aggressive or disrupting daily life. It is a reaction that comes up time and again in our focus grouping – even among Enthusiasts.

- Authenticity is key. Agency produced “sleek” content underperformed beyond the base. It can come across as manipulative and more political – less polished content with real people and experiences tested much better.

- Speaking of messengers, try an unexpected one. For example, when advocating for LGBTI+ rights (and speaking as a queer person myself), having a straight teammate on the football team talk about how their queer teammate is crucial to the team, is more likely to positively influence pro-LGBTI+ attitudes amongst football fans.

- Do not directly engage with misinformation. Engaging with this content tends to only further its reach. Rather than engage directly with misinformation, focus on putting out your own compelling content and narrative.

- Wording matters. Terms like, “climate justice” or “just transition” have the opposite effect of persuading middle audiences. In fact, people find them confusing. Talk about in more specific terms, like “How German innovation can help solve the climate crisis” or “When forests do well, we do well”.

- There is a fine line between motivation and apathy. For example, if you want to mobilise action against corruption, don’t talk about corruption as a systemic issue, even if it is. It is better to attach it to specific people or events. This is less likely to overwhelm middle audiences – ultimately inspiring inaction, as opposed to motivating and mobilising them.

A clever person once said that, as a campaigner and communicator, you need to encode what you want to say, within the context of what your audience wants to hear or can relate to – it changed the way I approach communication and is the best advice I ever got.

This analysis piece was initially published in the newsletter Speaking Moylanguage published by Tom Moylan. Original publication can be found here.

By Christian Skrivervik – Head of Press & Communication, European Movement International

- Eyes on the 2024 European ElectionsThe ‘Listen to People’ project will mobilise European citizens around European democracy and values ahead of the European elections in 2024 and strengthen the strategic communication and outreach capacity of civil society, activists, and change-makers. read more...

- Certain ghosts have never leftThe Italian election represents a watershed moment for the country and for the rest of Europe. There is growing concern in Brussels that the victory of the far-right coalition may turn Italy into a disruptive member state of the European Union (EU) with authoritarian trends and a reactionary political agenda antithetical to the Union’s fundamental values and priorities. At the same time, as war keeps ravaging Ukraine, support for democracy and democratic institutions has been shaken in Italy by the ongoing conflict. read more...

- The Case for Going Beyond the BaseYour base is your core audience - they are reliable in their support. They rarely need to be persuaded, but rather need to be mobilised. There are a few common traps that campaigners, activists and communicators can fall into when dealing with their base. read more...